periodiCALS, Vol. 9, Issue 1, 2019

Delaware County, with its breathtaking scenery in the Catskills, is home to the watershed’s headwaters, part of the largest municipal water supply in the United States. The entire system covers more than 1 million acres, delivering about 1 billion gallons of water daily through a vast infrastructure of reservoirs, aqueducts, tunnels and pipes to a million residents in Orange, Putnam, Ulster and Westchester counties and 8.6 million New York City residents.

Nineteen reservoirs on both sides of the Hudson River supply the New York City area’s water. Those fed by older watersheds close to the city and east of the Hudson require filtration. But west of the Hudson, about 125 miles northwest of Broadway, the Catskill-Delaware watershed’s six major reservoirs—Cannonsville, Pepacton, Rondout, Neversink, Ashokan and Schoharie—supply the unfiltered bulk.

Behind every drop of clean water traveling from Delaware County is a team of Cornell CALS scientists and Cornell Cooperative Extension (CCE) educators. For three decades, these experts have partnered with farmers, local and federal agencies and municipalities to develop custom plans to protect nearby streams from runoff, keeping drinking water pristine and affordable.

‘Science was the key’

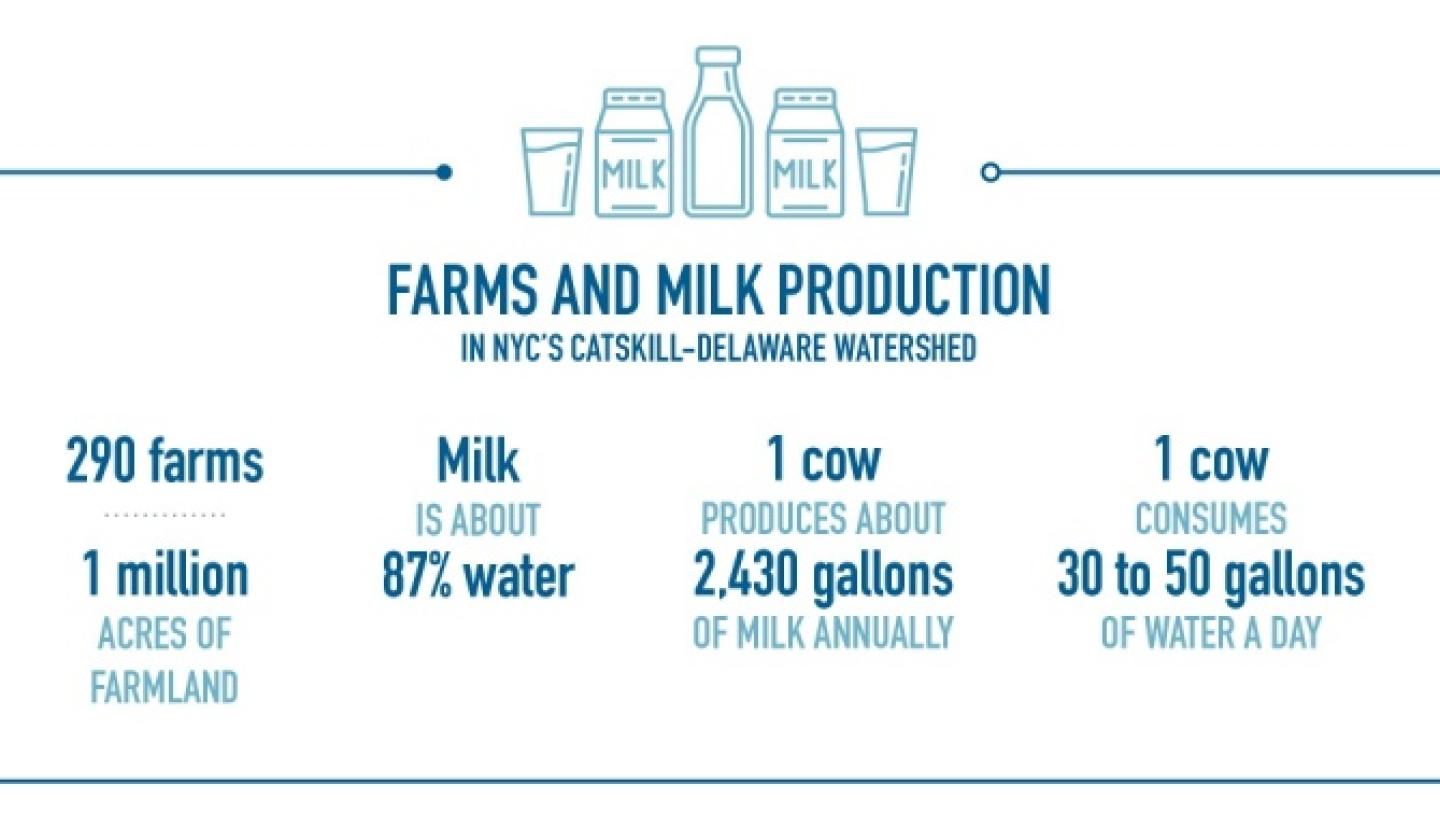

Agricultural land dominates the watershed. Cannonsville, one of the largest reservoirs, is surrounded by nearly 200 dairy, beef, sheep and goat farms. Across the entire area, hundreds of farms are home to thousands of cows. Their nutrient-rich manure poses risks to aquatic ecosystems and downstream drinking water supplies. In the late 1980s, new surface water treatment laws set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency took effect. The EPA told New York City officials that the state would need to build a filtration plant—with a likely price tag equivalent to nearly $10 billion in today’s dollars.

The New York City Department of Environmental Protection (NYCDEP), which has jurisdiction over the reservoirs and the surrounding land, received a “filtration avoidance” variance from the EPA. To qualify, the department needed to enlist the support of farmers, residents and other stakeholders in the watershed to keep the water clean.

The mission was straightforward but desperately complex in its implementation: Assist the watershed’s farmers in spreading nutrient-rich manure in an environmentally sensitive way, and balance the needs of animals and cropland so that the manure improves soil health but its nutrients do not trickle into drinking water.

For years, Cornell’s New York State Water Resources Institute had been providing practical knowledge for the region, so the agencies and farmers again turned to the university for additional scientific guidance. “The various organizations needed a framework to work together,” said Karl Czymmek ’86, senior extension associate in Cornell’s PRO-DAIRY Program, which assists New York’s dairy industry in economic development. “Science was the key,” he said.

The effort was accelerated by the Cornell Nutrient Management Spear Program, led by Professor Quirine Ketterings in the Department of Animal Science. Ketterings, who joined CALS in 1999, pioneered an approach that accounts for nutrients entering a farm system and where they all go. The nutrient mass balance software her team developed provides precise accounting to manage feed and waste.

“We can calculate how much phosphorus, nitrogen and potassium arrives at the farm and then how much of it leaves by way of milk production—and how much stays on the farm and is potentially subject to loss to the environment,” Ketterings said.

Professionals working in the watershed were among the few around the country to develop and execute this style of precision feed management, said Paul Cerosaletti ’89, M.S. ’98, an agronomist and dairy cattle nutritionist for Cornell Cooperative Extension of Delaware County.

“Importantly, we went from developing the science to implementation on a large scale across a number of farms. It’s more than a field-laboratory experiment,” Cerosaletti said. “It’s a water-quality program implemented across farms that’s efficient and fits into the conservation world.”

Tools to measure and prevent runoff continue to be improved. Mike Van Amburgh, Ph.D. ’96, professor in the Department of Animal Science, is the driving force behind the Cornell Net Carbohydrate and Protein System, now one of the most widely used cattle nutrition models in the world. CCE educators input a farm’s data into the model to evaluate the cattle rations and use the model’s output to develop detailed, precision feed management recommendations.

“We can tailor decisions to the forages and the cow to create a diet that maximizes cow health and minimizes the environmental impact of food production,” said Van Amburgh.

Efforts to mitigate farm runoff into the streams, along with upgrades to poorly functioning wastewater treatment plants proved successful. From the late 1980s to 2010, these projects caused the amount of phosphorus going into Cannonsville to drop by 55 percent, and 51 percent at nearby Pepacton Reservoir, according to the agency’s statistics.

‘The water starts here’

Seven full-time professionals from CCE offer best-management practices backed by Cornell CALS science and experience. They help nearly 300 farms manage soil excellence, produce high-quality crops, feed balanced rations, maintain herd health and, most importantly for New York City’s water supply, prevent manure runoff from wending its way into the streams.

Dennis Reinshagen tends to Holstein and Jersey cows in South Kortright, New York. On dry days, he walks the cows from the barn to a rotation of pastures for grazing. On average, each cow produces 2,430 gallons of milk annually, and Reinshagen perpetually organizes feed, milks cows and spreads manure. But he remains mindful that his farm and hundreds of others in the nearby area affect the drinking water of 9.6 million people in and around New York City.

“The water starts here,” said Reinshagen. “It’s something to be proud of. Water quality is important to people who live in New York City, and it is important to farmers, too, as the watershed helps keep agriculture sustainable,” he said. “A dairy cow drinks 30 to 50 gallons of water a day, and milk is about 87 percent water—so it’s in my best interest to maintain good water quality.”

The partnership among the farmers, governmental agencies and Cornell is unique. “You don’t really see this around the country, but it is an integral part of our watershed program,” said Craig Cashman, executive director of the Watershed Agricultural Council. “This kind of expertise is critical to watershed success. Cornell scientists and Cornell Cooperative Extension bring a skill set that is unmatched.”