This summer, we collaborated with Cornell Botanic Gardens to lead a 4-week online course for school-aged students called “Plants Have Families Too!” The material was adapted from the Botanic Gardens’ annual family botanical event, Judy’s Day, which was cancelled this summer due to COVID-19.

The class was led by three of us — Jesus Martinez-Gomez, Heather Philips and Clarice Guan — all graduate students in Plant Biology in the Specht Lab in Cornell’s College of Agriculture and Life Science. In collaboration with Raylene Ludgate, youth program coordinator at the Botanic Gardens, we developed the course material, delivered it and facilitated discussion — all via Zoom.

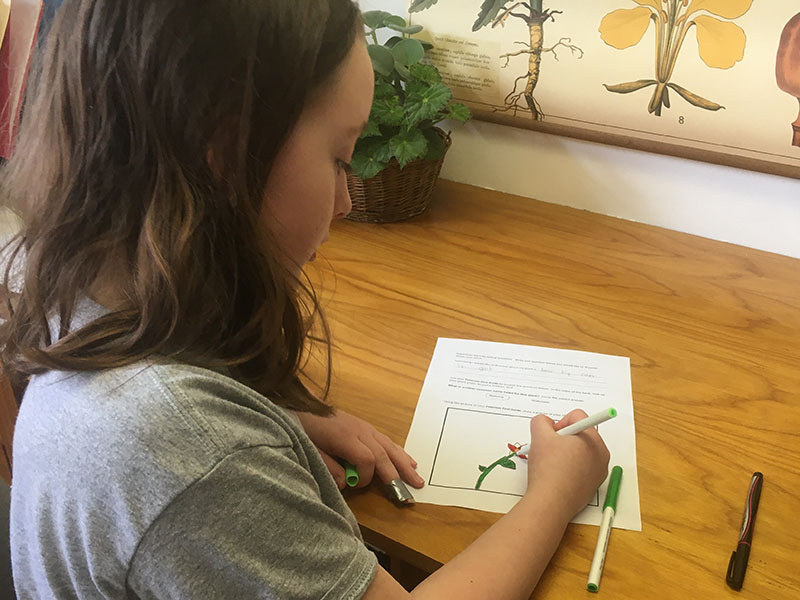

The course consisted of two 30-minute Zoom sessions on Mondays and Fridays. During the Monday sessions we introduced the students to a new set of plant families, and asked them to look for members of these families throughout the week. On Fridays, students presented the plants they had found, and asked questions about the plant families for that week. Over the course of four weeks, students learned to identify 10 different plant groups based on morphological features.

While working with young children via Zoom was more challenging than in-person teaching, we came up with a few quick tips for making online instruction both effective and fun: