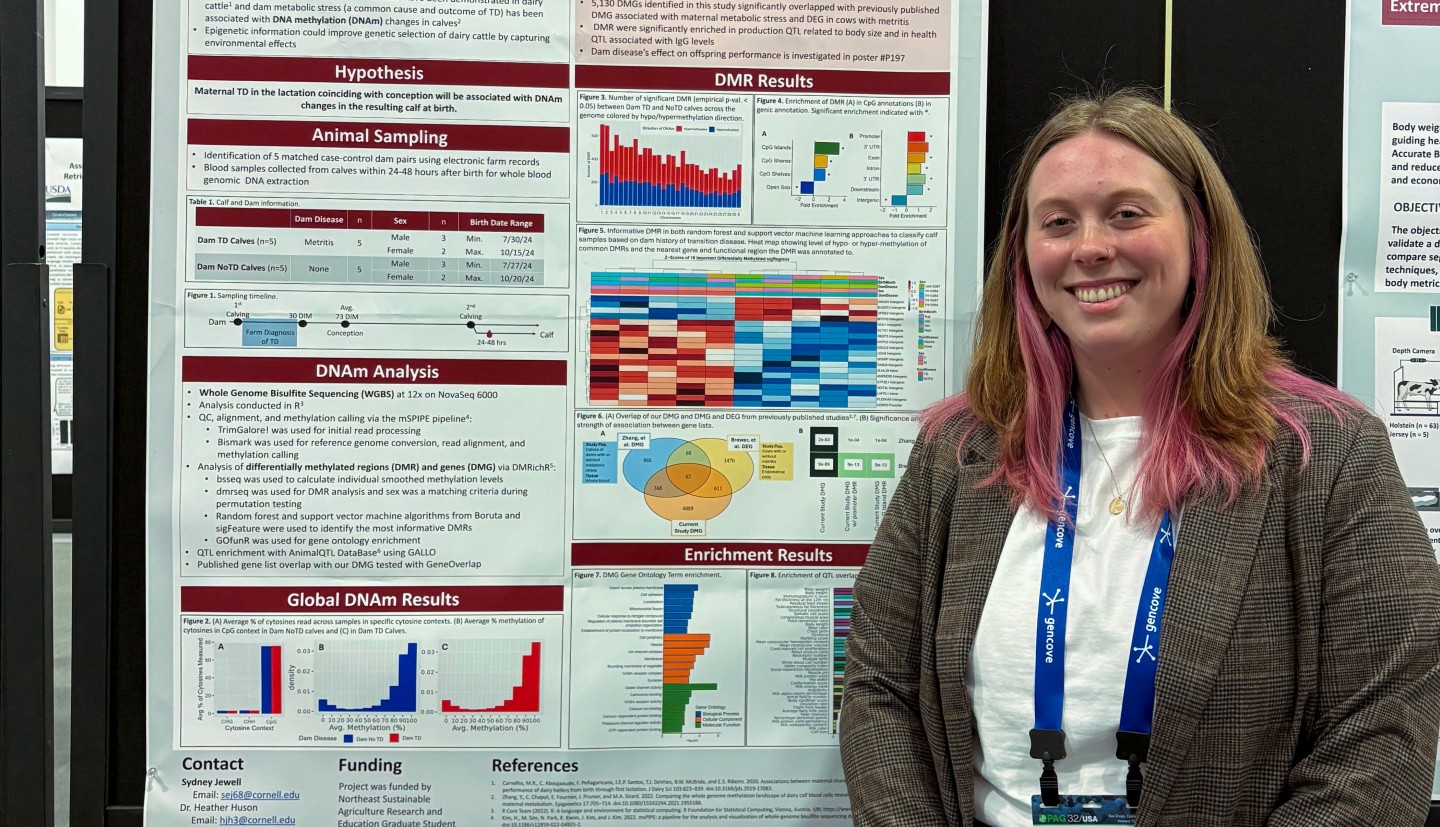

Sydney Jewell ’26 is a doctoral student in the Animal Science Department working in the lab of Heather Huson, associate professor of animal genetics. Sydney’s research focuses on epigenetics – the changes behavior and environment can cause to gene expression without changing the underlying DNA.

We spoke with Sydney about her research on dairy cows.

First, help us understand what the term “epigenetics” means.

Epigenetics refers to all the mechanisms the body uses to regulate gene expression. The genome of an animal includes instructions to make all the proteins the body could ever need, but not every cell needs to make all of those proteins all of the time. Epigenetic mechanisms allow flexibility in what genes are expressed, when and where. Epigenetic patterns are different between tissues, and can change over an animal’s lifetime and in response to environmental stimuli.

It might help to think of the genome as a cookbook. A cookbook is a large collection of recipes just as the genome is a collection of genes, each of which encode the recipe to make a specific protein. At the beginning of the week, you may mark what recipes you’ll make for dinners with sticky notes. You may choose easier or more difficult recipes, depending on how stressful you think the coming week will be and how much energy you will have to cook. Epigenetic patterns are kind of like those sticky notes; they indicate which genes are going to be expressed by the cell, and they are influenced by stress factors.