Cornell AES History

Acknowledgement

As a land-grant institution, we acknowledge that the commendable ideals associated with the Morrill Land-Grant Act of 1862 were accompanied by a painful history of prior dispossession of Indigenous nations’ lands by the federal government. As the largest recipient of appropriated Indigenous land from the Morrill Act and the institution that accrued the greatest financial benefit from that land, we also acknowledge Cornell University’s distinct place in this history. In addition, Cornell’s Ithaca campus sits within the indigenous homelands of the Gayogo̱hó꞉nǫɁ (the Cayuga Nation), members of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, an alliance of six sovereign Nations with a historic and contemporary presence in this area. This history compels our university to ensure that the values it upholds to make a positive impact on the world align with efforts to engage with and benefit members of all communities.

Introduction

At its best, the land grant mission epitomizes the ideals of:

- Relevant education available to all

- Research to address real world challenges of today and the future

- Extension interactions with the broader public to inform research and support implementation of research results

Its darker side is that the institutions and endeavors associated with that mission were built by capitalizing on the dispossession of indigenous peoples to profit from what were stolen lands. One cannot present a history of the Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station (Cornell AES) without acknowledging that there is truth to both of those perspectives.

Since its founding in 1879 Cornell AES has worked diligently to meet the ideals of the land grant mission, reliably supporting research aimed at those ideals and achieving tangible results that have improved the lives of New Yorkers.

Over the past 150 years, much has changed and our research goals and portfolio have changed in response. While there are threads that weave through our entire history – a focus on agriculture and food systems, and on the needs and aspirations of the citizens of New York – the approaches and techniques used have changed radically.

Today, we manage nine research farms in New York state, from Willsboro by Lake Champlain in the north, to Long Island in the south – representing the state's diverse growing conditions. We manage the largest, non-commercial greenhouse operation in the state. And we support more than 160 critically important research projects annually with our federal grant allocations.

At Cornell AES we remain dedicated to accelerating solutions to some of the world's most pressing problems of today and tomorrow, and to contributing to the vitality, resilience and long-term health of people and the planet.

Setting the Stage

The vision

Land Grant Universities were established by the original Morrill Act of 1862 (in the wake of the U.S. Civil War) to provide all qualified students, regardless of class, ethnicity, race, or gender, the opportunity for a university education. These universities were to merge education in practical matters (such as science and technology) with the more traditional liberal arts disciplines (such as history, literature, and philosophy).

At Cornell University, co-founders Ezra Cornell and Andrew Dickson White embraced these ideals and built them into Cornell’s 1865 charter: “to teach such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts, including military tactics, in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions of life.” Ezra Cornell captured this notion succinctly in the legend for Cornell’s seal, “I would found an institution where any person can find instruction in any study.”

How Land Grant Universities were funded – the "Land Grab"

The lofty ideals of the Morrill Act were sadly compromised by the methods used to generate funds for its new universities. Each state was granted one or more parcels of land by the U.S. government, to be used (sold, leased, or otherwise managed to generate funds) to support the cost of setting up the state’s land grant university. However, many of these parcels were obtained by previous dispossession of Indigenous people from their lands.

Cornell University has the painful distinction of being the largest recipient of appropriated Indigenous land, and also the institution that gained the most money from the “granted” parcels of land. As such, we acknowledge not only the physical presence of our university on the traditional homelands of the Gayogo̱hó:nǫ' (the Cayuga Nation), but also the fact that many parcels of appropriated lands contributed to funding the University’s establishment.

State senators Andrew Dixon White and Ezra Cornell win passage of the bill that charters Cornell University as the land-grant educational institution for New York. Consequently, the university is established.

While the Morrill Act had supported the universities’ educational goals, federal legislators acknowledged that research was also essential to improve agricultural practices. The Hatch Act of 1887 provided funds to each state for an agricultural experiment station (AES),

“…to conduct original and other researches, investigations, and experiments bearing directly on and contributing to the establishment and maintenance of a permanent and effective agricultural industry of the United States, including researches basic to the problems of agriculture in its broadest aspects, and such investigations as have for their purpose the development and improvement of the rural home and rural life and the maximum contribution by agriculture to the welfare of the consumer…”

The Hatch Act of 1887 (pdf)

Each state received $15,000 in federal appropriations, known as Hatch funds, to support the work of its AES. Appropriations to each AES have grown since 1888, but have been declining in purchasing power since the mid-1970s. Funds have shifted away from equal allocations per state to formula-based allocations.

Since 1887, Hatch funds have been an essential resource for innovation and problem solving in New York. Cornell AES Hatch funds support about 150 research projects every year.

1879 – Agricultural Experiment Station at Cornell established

In the 1870s, agricultural societies in New York (as well as other states) advocated for agricultural research. In 1874, President A.D. White announced the establishment of the University Farm to the New York State Agricultural Society. The University Farm was organized into an agricultural experiment station in 1879, directed by George C. Caldwell, albeit with no funding.

"The only funds at the disposal of the Station at present consists of the sum of two hundred and fifty dollars, given by Miss Jennie McGraw, for the printing of the report. All the work of the Station has therefore been volunteer work, and has been limited, of course, by the amount of time not required for professional duties in the University."

Two years later the Cornell University Board of Trustees provided the new experiment station with some funding. The Board’s support did not last long!

Experiment Station Appropriations from Cornell Board of Trustees, 1881-1886

Year Appropriation

1881-82 $1,000

1882-83 1,145

1883-84 750

1884-85 150

1885-86 0

Against All Odds: Isaac Roberts' Achievements

The second director of the Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station (Cornell AES), Isaac P. Roberts, grew up on a farm in East Varick on the west side of Cayuga Lake. After moving to the Midwest as an adult, he returned to Cornell in 1873 to help manage the University Farm. He envisioned it as both a model farm and a practical laboratory for investigation and instruction.

Roberts’ excellent handling of the farm led to his appointment in 1887 as the director of the experiment station with its newly-recieved $15,000 allocation of federal funds from the Hatch Act. Roberts was appointed director in May and told he had until the end of June that same year to spend or lose the funding allocation!

Professor Comstock was engaged to make plans for the first ever insectary to be built, which he drew up in just two days. Cablegrams were sent to a professor who happened to be in Europe to procure equipment that could not be had in the U.S. Having managed to spend the funds well, Roberts was also confronted with the congressional requirement for a report of the progress of work at the (barely established!) experiment station. Ever resourceful, he turned to as-yet-unpublished research bulletins to assemble the first ever report of work at Cornell AES.

Liberty Hyde Bailey, a Cornell Treasure

The third experiment station director was Liberty Hyde Bailey, appointed in 1903 as both director and the first dean of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at Cornell. Bailey believed that research, education, and extension to address agricultural challenges was equally as important to the University as were traditional areas of focus such a cultural, ethical, and legal issues. He also promoted a program of nature study in rural schools, designed to increase appreciation for the countryside and build knowledge of the natural processes on which successful farming depends. This focus from a century ago is reflected in current-day emphases on nature-based and regenerative agriculture. Bailey believed in education for women, and appointed the first three women professors to Cornell University’s faculty. Truly, Bailey was a profound thinker whose ideas were sometimes way ahead of his time.

"The service of the famer to society is not merely as a producer of supplies. The rural range is a type of life, and one of the great sources of citizenship. It is our nearest approach to a permanent society. It does not move itself in search of work, nor ever find itself out of employment, nor is ever closed by strikes or lockouts, nor even temporarily suspended by commercial conditions. It is as much a part of the order of things as the face of nature against which it works. To measure the farmer’s relation to society solely in terms of supplies or of economics is like measuring the weather and the soil by the rules of the countinghouse."

[What is Democracy? L.H. Bailey, 1918, p.114-115.]

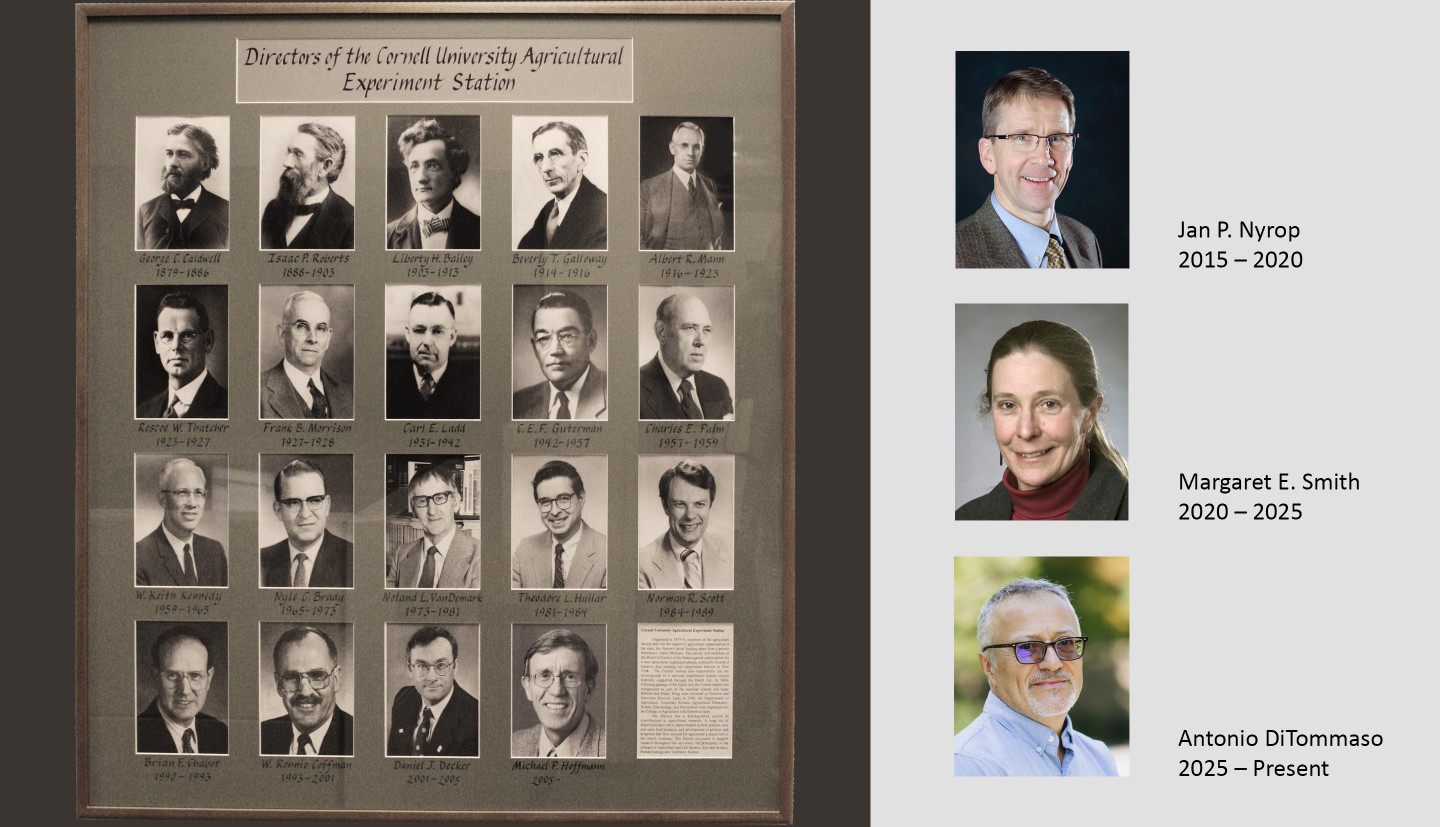

Directors

Cornell AES Directors

1879-1886 George C. Caldwell

1888-1903 Isaac P. Roberts

1903-1913 Liberty Hyde Bailey

1914-1916 Beverly T. Galloway

1916-1923 Albert R. Mann

1923-1927 Roscoe W. Thatcher

1927-1928 Frank B. Morrison

1928-1931 Albert R. Mann

1931-1942 Carl E. Ladd

1942-1957 C.E.F. Guterman

1957-1959 Charles E. Palm

1959-1965 W. Keith Kennedy

1965-1973 Nyle C. Brady

1973-1981 Noland L. VanDemark

1981-1984 Theodore L. Hullar

1984-1989 Norman R. Scott

1990-1993 Brian E. Chabot

1993-2001 W. Ronnie Coffman

2001-2005 Daniel J. Decker

2005-2015 Michael P. Hoffmann

2015-2020 Jan P. Nyrop

2020-2025 Margaret E. Smith

Since 2025 Antonio DiTommaso

Photo Gallery

Cornell Orchards

Orchard workers are spraying the trees, using a horse-drawn wagon.

Lab at the Cornell Orchards

After the harvest, a pomologist researches controlled atmosphere storage of apples in the lab at the Cornell Orchards.

Liberty Hyde Bailey Conservatory

The first Bailey Conservatory was constructed in 1931 by Lord & Burnham, the premier greenhouse suppliers at that time. The current conservatory was built in the same location and continues to house a fascinating collection of rare and exotic plants.

Long Island Horticultural Research & Extension Center

1970s: CALS Dean W. Keith Kennedy (third from left) and Cornell President Frank H. T. Rhodes (fourth from left) visit the Long Island Horticultural Research & Extension Center.

Research in Greenhouses

Martha Mutschler, faculty in the Department of Plant Breeding and Biometry, researches growth of tomatoes in the 1980s.

Guterman

In 1968 the Guterman Bioclimatic Lab was launched. For its 50th anniversary Jeff Guterman and his wife Jean visited the facility. Jeff is the grandson of Carl Guterman, director of the experiment station from 1942-1957, and the lab's namesake.

Roberts Hall

The Cornell AES leadership and administrative team is located in Roberts Hall, picture here around 1920 and named after Isaac Roberts, 2nd director of the experiment station.