In January, Elmer Ewing’s article on the genetics of pea seed resistance to rot -- based on his doctoral dissertation research -- was published in the Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science.

What makes this news? Ewing received his PhD from Cornell in 1959. Yet the journal’s editors found his research still relevant 65 years later.

“It was worth the wait,” says Ewing, professor emeritus in CALS School of Integrative Plant Science, now 92 years old. “In my whole career, it’s the most satisfying research I’ve done.”

Ewing built his reputation as a global expert in potato physiology at Cornell, and served as chair of the Department of Vegetable Crops and later Fruit and Vegetable Science from 1982 to 1996. But his pea seed-rot resistance story starts when he arrived in Ithaca in 1954 after earning degrees in chemistry and horticulture at the University of Illinois.

“I wanted to use chemistry and horticulture to help feed hungry people,” Ewing recalls. After completing two years of coursework on campus, he traveled to Rockefeller Foundation’s Mexican Agriculture Program (where the seeds of the Green Revolution were taking root) to conduct a year of field research on pea seed rot.

Old data, still relevant

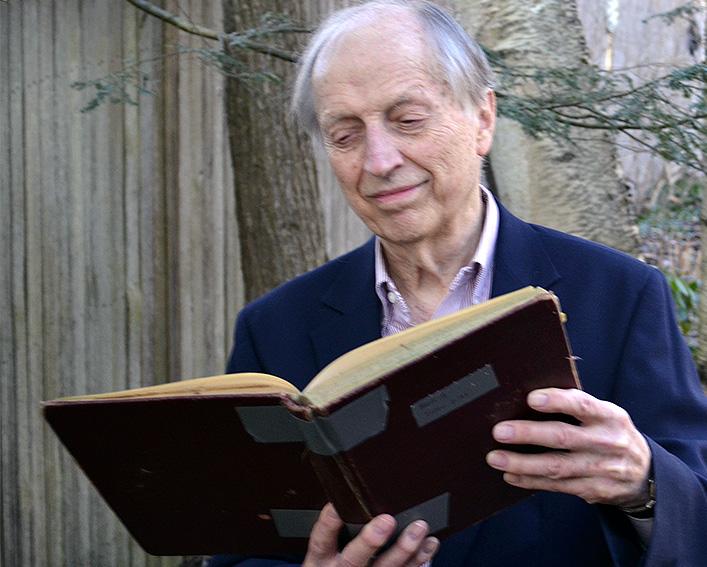

10 years after retiring, Ewing revisited his pea studies, motivated by the trend to reduce fungicide use in food production and the recognition that tannins can be healthful phytochemicals. Here he reviews the original notebook (visible on the ground in top photo) where he recorded data from his experiments.

While in Mexico, Ewing isolated the causal organism – Pythium (now Globisporangium) fungus. He also found that seeds from purple-flowered peas were highly resistant to rot whereas the more common, white-flowered ones were very susceptible.

Ewing returned to Ithaca and conducted additional experiments, demonstrating the key to high resistance lay with seed coat tannins. He also found that pink-flowered peas had a different kind of tannin and were slightly less resistant than purple-flowered peas.

Making connections

But before Ewing could finish his dissertation, he was pressed into service as an instructor, and soon after wrapping up his dissertation moved into a faculty position that focused on potato research.

“At the time, there wasn’t a lot of interest in my pea work because the standard solution for seed rot was just to treat the seeds with a fungicide,” recalls Ewing, who squeezed in a few more pea studies around his potato research until the mid ‘60s. Moreover, the tannins responsible for resistance also discolored cooking broth and imparted an astringency detectable by some.

In 2016 – 10 years after he retired – Ewing decided to revisit his pea studies, motivated by the trend to use fewer fungicides in food production and the recognition that tannins can be healthful phytochemicals. Forced to don a mask to avoid breathing the accumulated dust on his old lab notebooks, Ewing double-checked his decades-old data with the aid of a magnifying glass.

Ewing’s efforts intensified during the pandemic. He teamed up with Norman Weeden, a Montana State University pea geneticist who formerly worked at Cornell AgriTech, and recruited Ivan Simko, a former postdoctoral associate of Ewing’s who is now a USDA-ARS lettuce breeder, as co-authors for the paper. The team collaborated with Sheng Zhang and Elizabeth Anderson at the Cornell Institute of Biotechnology’s Proteomics and Metabolomics Facility, who used modern methods to confirm and expand on Ewing’s tannin identifications from the '50s.

“Dry peas have become a vital source of protein in many parts of the world,” notes Ewing. “Unlike the white flowers characteristic of garden peas, many varieties of dry peas have colored flowers.”

The study’s most important finding was that -- compared to purple-flowered dry peas -- pink-flowered ones have a different type of tannin, one reported to tie up less iron when consumed. The findings also suggest pink-flowered peas still have sufficient seed rot resistance that they can be grown without treating seeds with fungicides.

“Surprisingly, it seems no one had noticed the association between flower color and the kind of tannin in the seed coats,” says Ewing. “Science has become so specialized that it is hard to make connections between the old-fashioned genetics we used and modern disciplines such as plant pathology and chemistry. With helpful advice from experts in these fields, we were finally able to make the connection work.”

Keep Exploring

News

Report

- Cornell Cooperative Extension

We openly share valuable knowledge.

Sign up for more insights, discoveries and solutions.