Joint Cornell-Makerere project finds surprising results translating gender training program to an online environment

In 2013, when team members for the NextGen Cassava project set out to find a gender training program for crop breeding teams, they came up empty handed. Yet from this initial frustration grew an ambitious effort to create an intensive, applied and personal gender training model for agricultural researchers, Gender-responsive Researchers Equipped for Agricultural Transformation (GREAT) project, a collaborative effort between Cornell and Makerere University, in Uganda. Adapting this training model to a Covid-19 virtual world, however, was no easy task – but yielded unexpected results. Here we share some early lessons learned from our first effort at delivering an online course.

For decades the development community has recognized that agricultural interventions like crop breeding affect men and women differently – being unresponsive to (or even unaware of) these differences can produce harmful consequences for many of the people development efforts attempt to help. And for crop breeding in particular, not knowing who you’re breeding for risks spending billions of dollars on crop varieties that may sit unused.

While some gender training programs did exist, these tended to treat gender as a set of tools to learn, and relegated the work to gender specialists working in isolation – an “add gender and stir” approach that ignored the complex reality of gender as a pervasive social construct, and failed to take a holistic approach to affecting changes in how research is carried out.

To address this, the GREAT project has spent the past five years fine-tuning and delivering intensive training courses for teams of agricultural researchers from across sub-Saharan Africa, using an interdisciplinary, team-based approach focused on challenging preconceptions about gender, framing it in deeply personal terms. It’s a model that relies heavily on direct face-to-face interaction – a model that suddenly had to be reimagined entirely for our Covid-19 world.

This past March the GREAT project did just this – trimming 112 hours of in-person instruction into a 27-hour, virtual course, with 53 researchers joining from 14 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Naturally, we wondered what could be lost in the transition. How well would the interpersonal sessions play out over Zoom and Google Classroom? How could we replicate the team-based, collaborative learning space if everyone was tuning in from disparate locations? Here we’ll share some of what worked, what didn’t, and what we’ve taken away from this experience.

Getting personal with Google Classroom

Surprisingly, the most personal components of the course ended up translating best to our virtual delivery.

Quite ironically, the level of discourse and dialog in the virtual course’s asynchronous parts allowed participants and trainers alike to connect and engage in ways that simply haven’t been possible in our in-person courses.

For our in-person courses, the first two days are spent laying the foundation for a deeper understanding of why gender matters in agriculture, in research, and for the researchers themselves – what we call ‘getting personal with gender.’ This foundation frames the following sessions on tools, methods and research design, providing a lens for them to view all the subsequent learning through, and in many instances, provides an ‘aha!’ moment, where participants suddenly come to realize why they’ve been hearing about gender for so long. This, in addition to the interdisciplinarity of the course and a focus on application across the entire research cycle, is what sets GREAT apart from most other gender training offerings out there.

While our in-person courses use numerous exercises, breakout groups, and ‘energizers,’ participants end up sitting for long hours at a time, taking in lectures. The busy schedule, it seems, actually impedes interaction and dialog.

During the virtual course we quickly realized that the level of engagement between trainers and participants was far higher than even during our in-person courses. Using Google Classroom for asynchronous engagement, participants were able to share detailed reflections and get detailed replies back from their instructors. With greater one-on-one dialog and feedback, participants were able to access more direct feedback, and removed from the pressures of sharing in a large group setting, there was a sense that people could be more open than they would be in a large group setting.

Quite ironically, the level of discourse and dialog in the virtual course’s asynchronous parts allowed participants and trainers alike to share and engage in ways that simply haven’t been possible in our in-person courses.

The cooling effect of Zoom

While the asynchronous engagement fostered greater dialog and exchange, the live Zoom sessions had the opposite effect. With a course spanning multiple time zones, limited attention spans for online sessions, and participants’ needs to juggle multiple demands, our synchronous Zoom sessions were much shorter than our in-person lessons, leaving less room for engagement and Q&A. Moreover, with a ‘room’ of 50+ Zoom participants, varying degrees of comfort speaking up online, and fewer chances for ice breakers and mingling over coffee breaks, participant engagement was much more limited to a few vocal people than we experience in person.

Moreover, the most vocal participants were almost entirely men, despite women making up 43% of the cohort. While women were somewhat better represented in the chat box, the lack of women participating verbally in a gender training raises interesting questions around deeply ingrained roles and behaviors – ones that don’t necessarily change quickly, or in response to cognitive shifts (and this is assuming that cognitive shifts were taking place). To what degree is equity in participation a reflection of course learning? What could / should GREAT do to see this as a ‘teaching moment,’ reinforcing course concepts by illustrating that translating gender training into concrete action takes intentionality and self-reflection – it takes applying a critical gender lens back on one’s self.

In the future we need to take extra care to ensure that different people are comfortable engaging and sharing, and explicitly raise the issue of gender imbalances. More broadly, we can facilitate participants to use a suite of options available to speak up, including being more active in the chat box discussion, or creating more opportunities for small-group discussions, ‘coffee hour’ networking, and other less intimidating avenues for engagement. But we can’t ignore the elephant in the room – especially when it provides an opportunity to reinforce our message.

Giving time to concepts

With less ‘in-class’ time, and a greater reliance on readings and asynchronous assignments, one area where participants struggled was in internalizing key gender concepts. Through chat room comments, and later in team presentations, some core concepts didn’t sink in to the level we were looking for. Concepts take time to be understood and internalized, and in our in-person courses we’ve seen that it’s okay to allow for such struggles, as long as we leave time to work through these – something that didn’t happen for this course due to schedule changes and a compressed time frame.

More broadly, this is an area to flag for future course MLE to help us better gauge how effectively our online delivery fosters deeper conceptual understanding.. Does extra space help deepen conceptual understanding? Do we need to identify alternative delivery methods, or prioritize delivering material like this in person for future hybrid courses? Shifting deeply rooted norms and internalized biases takes time, and while our one-to-one asynchronous engagement helped build closer dialog with trainers, we need to further examine how best to ensure that we give participants the critical deeper understanding needed to change norms and behaviors, and have appropriate measurements to capture how well we’re doing in this area.

Resisting the urge to scale up

While virtual learning is often seen as a means of reaching audiences at scale, for GREAT this course was a cautionary lesson against following in this path – and a reminder that not all material translates to online learning in the same way.

Working closely with an online learning expert at Makerere University, Thomas Enuru, allowed us to see how a course like ours differs greatly from the sort of quantitative courses Enuru usually manages, focused on technology-related topics. Where he would typically be able to automate assignment grading for hundreds of participants at once, the qualitative engagements GREAT uses to draw out nuance and personal discovery around gender require a level of time commitment that makes scaling up difficult – and render automated grading counterproductive.

In many respects, shifting online required new roles – and additional support – to make the course run smoothly. Aside from the need to create and adapt asynchronous assignments, we needed additional support to manage Google Classroom engagement, technical support, chat room facilitation for Zoom sessions, and more. While some of this work would diminish over time – e.g., developing assignments for Google Classroom – we’ve learned that online delivery for a course like this simply requires intensive backstopping support.

Add to this the challenges we faced around fostering deeper conceptual understanding, it’s clear that delivering online courses like GREAT requires small class sizes, where trainers and facilitators can take the time and care to ensure that key concepts and ideas thoroughly sink in, that we reach the deeper roots that guide our assumptions, biases and norms. ‘Going big,’ for GREAT, would mean sacrificing what makes this training different from other gender courses.

Measuring engagement – a double-edged sword

Paradoxically, when it came to measuring participant engagement, the online course was both easier and harder. With more assignments, greater instructor / participant dialog, chat box comments, and written records, both the asynchronous and synchronous parts of the course created new opportunities to keep track of and assess student involvement. However, with participants attending from far flung locations and unreliable internet connections (Zoom sessions were available to stream online after each session), getting a sense for actual engagement in live sessions was far more difficult.

For this course we created a new position, online learning coordinator, staffed by Makerere’s Losira Nasirumbi Sanya, who helped structure and track online engagement. The role was a crucial one, and yet another reason that scaling up is challenging for a course like this. Monitoring engagement takes careful planning and lots of staff time, though we’ve learned valuable lessons from this first experience that will guide us in planning future online courses.

Finding our cost/benefit groove

Operationally, one of the biggest challenges for a training program like GREAT lies in finding a cost-effective delivery model. Bringing dozens of researchers together from various institutions across the continent translated into tens of thousands of dollars in fixed costs for flights, visas, hotel rooms and meals. With so much money going to travel, room and board, running a GREAT course is a costly affair, and given that many institutions still have slim budget lines for gender training, getting our costs down to an accessible level has led to continuous pressure on the project to search for a better balance between costs and quality

Moving online gives us a new avenue for reducing costs, becoming another item in a post-Covid menu of options for us to choose from, to mix and match in our quest to deliver a truly effective, accessible course that lives up to our standards.

Over the past five years we’ve experimented with ways to trim these costs, including shortening the course from two in-person sessions – bookending several months of field application – to just one session, thereby cutting travel costs in half. We’ve also delivered institution-specific courses, instead of our usual open-application courses, allowing two or three trainers to travel instead of 30-40 participants.

And yet each of these changes has tradeoffs: with single session courses we miss out on much of the application; institutional courses, meanwhile, come with their own tradeoffs, and lack the cross-institutional exchange of ideas and networking potential.

Moving online gives us a new avenue for reducing costs, becoming another item in a post-Covid menu of options for us to choose from, to mix and match in our quest to deliver a truly effective, accessible course that lives up to our standards. Such a hybrid approach would mean identifying which sessions could move online, which would best be delivered in person, and what material could be handled asynchronously before, during or after the in-person sessions. Some sessions are more amenable to online delivery in advance of a face-to-face session; as we gain more experience with online delivery, we’ll be better positioned to gauge which sessions work best in a remote setting.

Next steps

Going forward, most directly this experience will help us shape a planned ‘level 2’ GREAT course later this year, which may also be online if needed. Beyond this, however, we also see these lessons guiding future course decisions even after in-person instruction becomes a possibility again. We’re already thinking through the possibility of creating hybrid delivery models, where some material is delivered online, and some in person.

Moreover, some of our engagement strategies with Google Classroom can translate into better in-person delivery, with greater opportunity for assignments and engagement that creates one-one-one interactions with trainers, gives us more tools to track participant learning, and provides more introverted participants with additional avenues for contributing or asking questions.

And the applications don’t stop with our course design, either. GREAT trainers have appreciated learning a new pedagogical tool – for GREAT, and for their graduate students and the courses they teach in the university setting.

While the idea of online GREAT courses working seemed far-fetched in the past, we now see a new set of tools and options for us to deliver our courses more effectively, more accessibly, and at a lower cost. One thing that hasn’t changed, however, is our commitment to keep innovating and improving to deliver the best gender training program we can.

About GREAT

GREAT delivers training to agricultural researchers from sub-Saharan Africa in the theory and practice of gender-responsive research, seeking to increase opportunities for equitable participation and the sharing of benefits from agricultural research and improve the outcomes for smallholder women farmers, entrepreneurs, and farmer organizations across sub-Saharan Africa.

By building and engaging communities of researchers equipped with the skills, knowledge, and support systems to develop and implement gender-responsive projects, GREAT advances gender-responsiveness as the norm and standard for agricultural research.

GREAT is a collaboration between Cornell University in Ithaca, New York and Makerere University in Kampala, Uganda.

Keep Exploring

News

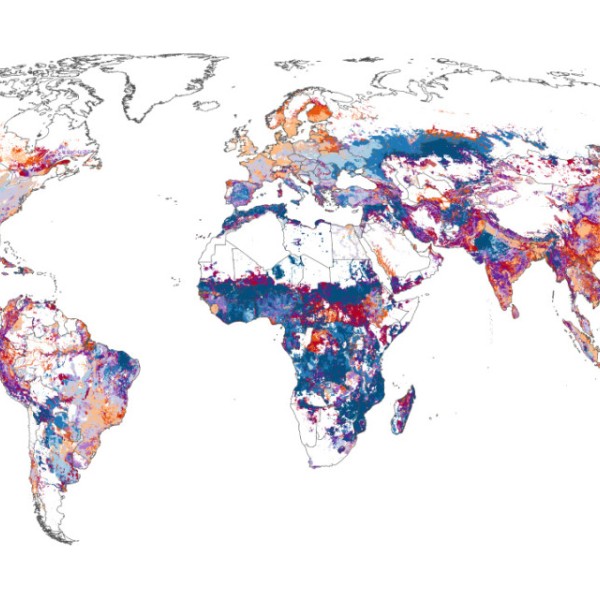

The new, high-resolution maps calculate global emissions from croplands by region, crop and source – enabling hyper-local mitigation.

- Ashley School of Global Development and the Environment

- Global Development Section

- Agriculture

Field Note

- Animal Science

- Agriculture

- Field Crops

We openly share valuable knowledge.

Sign up for more insights, discoveries and solutions.