How Ariana Constant ’09, MPS ’14 is driving equitable international development programs

As director of the Clinton Development Initiative, Ariana Constant ’09, MPS ’14 supports the sustainable development and resilience of African community farming groups. With two degrees from Cornell CALS and as a returned Peace Corps volunteer with deep experience working in Africa, Ariana advocates for impact-driven programs that encourage rural agricultural economic growth and resiliency. In her work she promotes a sustainable model of international development that prioritizes local expertise, equity and collaboration.

For three years I worked directly with farming communities in Senegal, one of the most mesmerizing places in the world, as an agroforestry extension agent. The job through Peace Corps allowed me to put my passion for international work into practice. There I was, a 22-year-old from New York City in rural Senegal fresh off my undergraduate degree from Cornell, primed to make an impact.

I worked closely with the community of Yongo with the Water and Forestry Service (L’Eaux et Foret) of the Senegalese Government, and with various local and international nonprofits. I’d often ride around on my bicycle to visit different farming communities and share attaya (tea) with the farmers. This was my first experience working in the international development sector and agriculture in general; for someone who grew up in Manhattan, it was a big change.

Working with these communities put me in direct contact with the lived experiences of those who called this beautiful place home. It was invigorating to ask questions about people’s day to day lives – the weather, what crops they grew, how they get to the closest market, what challenges they face, what they wanted to see for the future of their community. I’d ask about NGOs and government work too. I slowly understood that while a lot of investments had been made into agricultural trainings and even building up rural infrastructure such as community or school gardens, there was very little emphasis on community engagement and getting local buy-in, not to mention the sustainability of interventions put in place.

Early on, I realized that while goodwill and resources existed in abundance, the fundamental challenges that farming communities face were not being addressed.

Food and nutrition security, reliable and reasonable levels of income – these are things that matter most every day, yet the problems persisted. Farmers told me how they had been trained on the importance of planting trees to combat climate change. They had been told they sequester carbon.

I nodded, but thought to myself: how do farmer efforts in Senegal to plant trees impact their crop production and the amount of food they would be able to provide for their families or their revenue potential? I noticed that there was a disconnect between non-profits and farming communities when it came to communication and training. There was an issue in how some of these trainings were being framed, which resulted in fewer farmers understanding their importance and the urgency around the trainings and the application of interventions.

Re-envisioning the non-profit sector in rural Africa

Candidly, I left the Peace Corps a bit disillusioned with the non-profit world and international agriculture and development sector at large. I kept wondering why after decades of grant funding, supposedly allocated and deployed to help build resilience and improve livelihoods, there was little change. What was the disconnect? Was no one else aware of this? I came to see the need for a re-framing of humanitarian work that was focused on and driven by the communities that were set to benefit from these resources.

I returned to Cornell a few months after leaving Senegal to pursue a Master of Professional Studies (MPS) in International Agriculture and Rural Development (now Global Development). It was August 2012, and I was back on campus, surrounded by classmates from all around the world and engaging with professors with a great depth of expertise and diversity of experiences. At Cornell I put my energies into re-imagining the role and responsibilities of non-profits in the agriculture sector in Africa. It was clear to me that all stakeholder groups active in the sector needed to get involved. Everyone — especially the farming communities — needed a seat and voice at the table.

When communities are empowered to secure their own food and support themselves financially, economies grow, jobs are created, and communities become more resilient.

After graduating Cornell with my MPS I found a way to be a part of the change I wanted to see in the sector. I am now the Director of the Clinton Development Initiative (CDI), an initiative of the Clinton Foundation. President Clinton founded the CDI to empower smallholder farmers and their families to meet their own food needs while improving their livelihoods. CDI works to transform subsistence agriculture and catalyze social and economic change for farmers in Malawi, Rwanda, and Tanzania. CDI is actively working with more than 70,000 farmers across thousands of formal and informal farming groups, savings groups and cooperatives.

We think of ourselves as a business-oriented non-profit, intently focused on the type of work we do and how we do it. We ask ourselves questions like — if we were to leave tomorrow, what would be left behind? Does our work create or perpetuate a dependency on us? Or are we working to strengthen and revamp existing systems where farming communities, the private sector, government and other local businesses are able to thrive and access to information, financial services and markets? Are we putting people first?

Day to day we work with farming communities to form groups to collectively increase the quantity, quality, and consistency of their production while also improving access to markets and finance. Our colleagues are embedded within the farming communities we work with and are trusted advisors on all topics related to agribusiness. We focus on brokering relationships between farming communities and other stakeholders in the agriculture sector, training on topics such as entrepreneurship and organizational management. GDP growth originating in agriculture is about four times more effective at reducing poverty than GDP growth in other sectors (World Bank 2008a). We believe that the future of the sector lies in the hands of these communities and their ability to thrive.

A collective force for impact

At CDI we rarely go a day without talking about how best to work ourselves out of a job. Over the last 3 years, we’ve helped register 15 farming cooperatives in Malawi and increased the revenue of soybean producers in Malawi by 28% through connecting them to a market in Rwanda. We’ve distributed more than $300,000 in a revolving loan program to communities across Tanzania, Malawi and Rwanda. These efforts build a credit history for those same communities to access loans from banks directly. We’ve worked with thousands of farmers in Malawi and key supply chain actors to sell millions of pounds of high-quality soybean to the public-private partnership socially oriented business Africa Improved Foods in Kigali, Rwanda, which made a commitment to source more raw commodities from smallholder producers.

I do not envision a world where international nonprofits like CDI do not exist. Rather, I envision a world where donor funds are less restrictive.

I envision a world where we can work with communities and other stakeholders to more strategically spend funding on building more inclusive and equitable systems that don’t exclude or create dependencies for the most rural, poorest or most nutritionally deficient.

I envision a world where there is trust and confidence between local and international partners, and where equity between and across farming communities, markets and financial institutions is commonplace.

At CDI we believe this is just the beginning of a movement to strengthen farmers’ positions and power with the agricultural economy and drive regional economic growth.

About the author

Ariana Constant

Ariana Constant '09, MPS '14 is the Director of the Clinton Development Initiative, an initiative of the Clinton Foundation that drives community agricultural business development across farming populations in Malawi, Rwanda and Tanzania. Ariana works between New York and Africa to create partnership networks with governments, private sector, non-profits and civil society. Ariana holds both a B.S. in Natural Resource Policy and Management and International Agriculture and Rural Development (IARD) and a Master of Professional Studies in International Agriculture and Rural Development (Global Development) from Cornell University.

Keep Exploring

Field Note

- Dairy Fellows Program

- Animal Science

- Agriculture

News

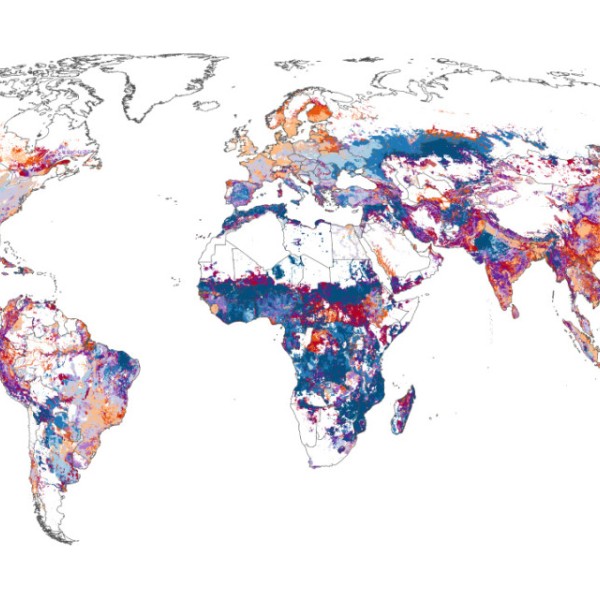

The new, high-resolution maps calculate global emissions from croplands by region, crop and source – enabling hyper-local mitigation.

- Ashley School of Global Development and the Environment

- Global Development Section

- Agriculture

We openly share valuable knowledge.

Sign up for more insights, discoveries and solutions.