But research sometimes points in different directions. So it can be hard for policymakers to decide where to dedicate limited funds, and how best to help farmers adopt the right crops.

Ceres2030, a global effort led by International Programs in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (IP-CALS), the International Food Policy Research Institute and the International Institute of Sustainable Development, is employing machine learning, librarian expertise and cutting-edge research analysis to use existing knowledge to help solve these and other challenges – all aimed at eliminating hunger by 2030.

“We have an opportunity to achieve higher food security, create a safety blanket to cope with climate shocks and improve overall livelihoods,” said Maricelis Acevedo, associate director of IP-CALS’ Delivering Genetic Gain in Wheat Project and lead author of a forthcoming Ceres2030 study. “Synthesizing the available scientific evidence can help scientists, policymakers and governments understand how to increase the utilization of climate-resilient crops.”

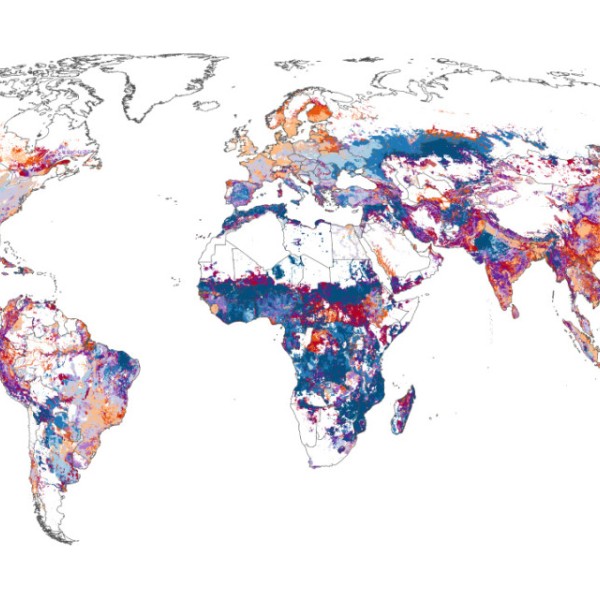

Climate-resilient crops are at the center of one of Ceres2030’s eight research questions, which seek to identify interventions that will improve the lives of the world’s poorest farmers while preserving the environment. The questions – built around the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals – range from reducing food loss to providing better agricultural skills training for young people in Latin America, Africa and Asia.

“We want to generate better evidence; we want to figure out what solutions we should be investing in right now,” said Jaron Porciello, primary investigator of Ceres2030 and associate director of research data engagement at IP-CALS. “For good public policy, we need to know what works. Science is always looking for the next horizon. It’s not a criticism of either side. But these are two adjacent systems that want to interact. They largely rely on the same evidence base for answers, but we don’t have a bridge to help them.”